By Debbie Gardner

debbieg@thereminder.com

What does a “traditional” Christmas feast look like?

Thinking back to the holidays of my youth, I realize “Christmas” looked very different depending upon whom we were visiting.

With my mother’s Portuguese family – which celebrated with a big holiday meal on Christmas Eve – the feast meant fried codfish balls, big casseroles of tuna fish (or sometimes rabbit) and rice, deep dishes of a sweetened rice pudding, and fluffy fried dough sprinkled liberally with sugar.

With my father’s family – my grandmother had been a farm girl from upstate New York – Christmas night dinner meant a roast turkey with vegetables, and lots of sweets including a dark, chewy, round “pudding” served with a frosting-like confection called “hard sauce,” a home-made fruitcake that was dense with candied cherries, pineapple and bright green, sweet fruit pieces, a soft cookie studded with candied cherries and walnuts, a big bowl of mixed nuts in the shell, and ribbon candy.

My current Christmas night dinner resembles none of these – I serve a pineapple-studded and sauced ham, the much-requested casserole of cheesy au gratin potatoes, mashed carrots and turnips – a family favorite I inherited from my mother-in-law – green beans and a plethora of finger-food sweets – mostly cookies – for dessert.

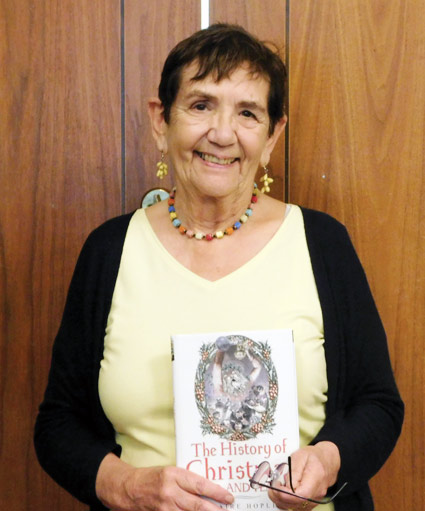

But this is the way of Christmas feasting, according to food historian and cookbook author Claire Hopley of Leverett, MA. What was popular in times past aren’t necessarily on our tables today – or are they?

“Christmas in fact plays fast and loose with tradition. It creates new frolics, picks new foods as must-haves, and incorporates charming customs from other countries,” Hopley writes in the introduction to her historical cookbook-cum-holiday timeline, “The History of Christmas Food and Feasts.” “Equally, Christmas can be cavalier about the past: it forgets or abandons old customs, then, perhaps, later revives them.”

Prime had the privilege of catching up with Hopley at one of the many food history classes she’s hosted over the years at the Springfield Museums. Offered in early November, her “Why Pie?” class touched on the history of both Thanksgiving and Christmas in America in addition to why the lowly pie is such a ubiquitous part of feasting, even today.

But it was Christmas, and the foods and traditions we spend time preparing and sharing at that holiday that was the focus of our chat, and Hopley, who said she undertook the study of Christmas foods and feasts primarily because she is “interested in history, especially social and culinary history,” painted a picture for me of how our tradition of feasting in December actually has its roots in Roman celebrations that existed long before the early Christians began celebrating Christmas.

Why we feast at all

“You will see in my book that the underlying traditions [of Christmas feasting] come from Saturnalia,” Hopley explained. That ancient week of celebrating, which ended on what today would be Dec. 23, honored the Roman god Saturn, the patron saint of agriculture. “Temples and buildings were decorated with greenery [and] masters and slaves feasted and drank together,” Hopley notes about this ancient festival in “A History of Christmas Food and Feasts.” Early Christians simply adjusted the feast to include Dec. 25, when they honored the birth of Christ. A week after the end of Saturnalia, Hopley writes the ancient Romans celebrated New Year’s – or Kalends – with more feasting and lavish gift giving. “The similarity between the lavish presents and open-handed expenditures of Kalends and today’s Christmas is easy to see,” Hopley writes. “On the following days the Romans entertained themselves with gambling – another tradition that long continued and survives today in the board games and electronic games still popular as Christmas presents.”

Our ‘modern” holiday fare

And though Christmas celebrations may trace their roots back centuries, what we today think of as the Christmas feast today draws from customs that actually began in the 19th Century and Victorian England. According to Hopley, a lot of what we now consider Christmas feast traditions can be traced back to the writings of popular authors of the time, such as Washington Irving – who wrote a collection of Christmas stories in 1822 – and Charles Dickens, who extolled the virtues of Christmas celebrations in several of his novels. Think “A Christmas Carol” – and the big bird hanging in the window of the butcher’s shop that Scrooge sends the street boy to go and buy for Bob Cratchit’s family. Everyone gathered around the table sharing a special meal – be they the wealthy class or the working poor – soon became a symbol of the holiday.

But why a feast at that time of year?

Hopley said this actually had more to do with practicality than actual religious traditions.

“Farmers had to kill a lot of their animals in November, because in cold climates they didn’t have anything to feed them … so basically for that reason, and because it was hunting season, people had meat in December” and they didn’t really have reliable ways to preserve it, she said. “It was a time of fairly plentiful food since the harvest had been gathered in and animals had been slaughtered, so it was an opportunity to eat [well] before winter set in.”

Take for example, that turkey or goose we often roast to a golden brown to serve as a showpiece for our Christmas table, as my farm-born grandmother always did. According to the lore Hopley shared during her “Why Pie” talk, that tradition comes directly from the English custom of serving fowl of all types – including swan and heron – as the centerpiece of lavish celebrations. As she writes in “A History of Christmas Food and Feasts” in Medieval times, it was even customary to serve the birds with tail feathers intact and spread in display, and to sometimes actually gild the cooked bird for dramatic effect.

The beef roast that some families today might serve, according to Hopley’s book, can be traced back to 18th and 19th century English Christmas feasts, where even a less well-to-do family could take a joint of mutton or roast of beef to the local baker’s shop (baking ovens not being common except in the richest homes) to be cooked for the holiday meal.

Other common Christmas foods today, such as smoked hams and pickled dishes – my grandmother used to serve a sweet pickle made from watermelon rind at holiday time – were other Christmas specialties that Hopley said had end-of-the harvest roots.

As for that selection of dense raisin pudding, fruitcake, ribbon candy and nuts that were also a part of my grandmother’s Christmas table, Hopley notes that focus on luxury – or seldom-eaten foods – is another hallmark of winter feasts that began in Roman times, disappeared during the years of the Pilgrims and the Reformation in England, only to find revival as the Victorians embraced Christmas celebrations once again.

“Historically, until quite late in the 18th century, sugar was terribly expensive, so anything sweet was ‘special,” and Christmas is a feast, so anything special can go in a feast,” Hopley said. Today, some of these “special” Christmas foods have morphed from the dried fruit baked goods of old into expensive wines and cheeses, and treats such as gourmet chocolates and decadent cakes.

“One of the things you see at Trader Joe’s are imported things, the Scottish shortbreads, the Italian Panna Cotta – it’s the idea of having something special [for the holidays] because it’s too rich or good, or you can’t afford it for everyday,” Hopley said.

A melting pot of influences

After the 19th Century there was a large influx of immigrants in both England – where many of our modern concepts of Christmas feasting originated – and America, and Hopley said these new residents brought with them feasting traditions of their own.

For example, Hopley said the codfish balls and tuna fish and rice dishes that graced the Christmas Eve table of my mother’s Portuguese family were traditional fare in Catholic homes, which customarily observed fasting until Christmas day.

“The Italians do it, the Polish do it” as well, she noted.

In fact, the plethora of dishes we look at as holiday foods – from eggnog to gingerbread, flan to piroggies – reflect the melting pot of American culture.

“I think in America, the many immigrant groups have all brought their own customs and lots of these have become mainstream, so America has many [Christmas] traditions and a big range of foods.

For Hopley, herself a native of Britain who now splits her time between the States and her homeland, Christmas feast favorites include “traditional English foods such as mincemeat and Christmas pudding,” she shared. “I also love marrons glaces, which are a French Christmas luxury. I love the Nutcracker, too.”

But no matter how we celebrate the Christmas feast today, Hopley said one thing has not changed from its roots in the Roman celebration of Saturnalia – “The fundamental concept is having a good time with lots of food and drink.”