By Debbie Gardner

debbieg@thereminder.com

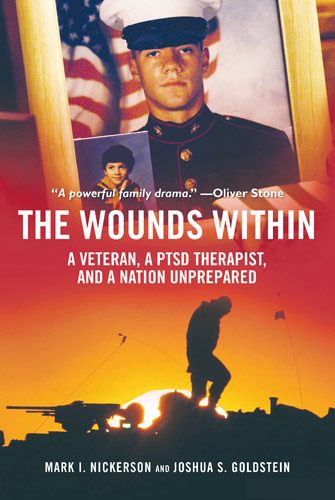

Mark Nickerson, LICSW, has conducted an individual & family psychotherapy practice in Amherst, MA, for 30 years. He lectures, trains and consults locally, nationally and internationally on a number of mental health issues, including the needs of combat veterans and their families. Nickerson is also the author of “The Wounds Within” – chronicling Western Mass Iraqi war vet Marine Lance Corporal Jeff Lucey’s struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and eventual suicide, and his family’s 10-year battle to reform the Veterans Affairs system and end the stigma around military-related mental health issues.

With Veteran’s Day approaching, PRIME spoke with Nickerson about PTSD and how families can help returning vets cope.

Q: The aftereffects of battle have always plagued those who serve in some way. Has modern combat made returning to civilian life more difficult for today's servicemen and women?

It’s always hard to compare different eras in our society and different conditions of war. The Iraq and Afghanistan wars have had many unique features including no clear front lines, difficulty identifying the enemy, and the ever-present threats of improvised explosive devices (IEDs), all of which can leave a combat veteran on edge scanning for danger during the day and sleeping with one eye open at night. Many have returned deeply saddened as they remember buddies who did not make it home. Some miss the comradery and the action, however dangerous it was.

Almost 50 percent of military-based participants in these wars were “civilian” – they were in the Reserves or National Guard – and after their tour moved quickly into the community and away from military life and familiarity. Many female veterans have faced gender-based mistreatment by male comrades and the extent of this is still emerging.

In general, veterans do best when they can find a meaningful way back into family, friends and meaningful work. Those that are without work or homeless fare poorly.

Q: Today we call the most serious post-combat effects PTSD, after World War I it was “Shell Shock.” As a clinician, do you believe PTSD is more prevalent among today's veterans, or are we more aware of it?

Even during the Civil War euphemistic terms like “exhaustion” or “soldier’s heart” were used to describe a normal human response to prolonged or acute battle conditions. Some use the term PTS to normalize the reaction by taking the word “disorder” out of the description. And yes, I think as a culture we are much more psychologically savvy than in the past. We are both more aware of the symptoms and more supportive of the need to recover from the psychological wounds of war.

However, the internal barriers for a warrior to seek help remain strong and sometime impermeable to reason. The military does a lot to build toughness before battle but not enough to prepare warriors to know they will need to recover from what they do or see in the combat zone. Pulling the trigger and handling the memory of the target as it dropped are two very different psychological processes. Our society does a lot to teach our young men and women attitudes of tolerance for different cultures. That makes it harder to see the “enemy” as evil.

Q: Are there signs and symptoms of PTSD that family and friends should be aware of? How can they help?

It is important to remain curious about how the veteran is doing without being intrusive. It is common for veterans to think or say, “you can’t understand.”Don’t let that stop you from trying. Don’t make assumptions, but don’t be afraid to ask questions and show your concern. I find it most useful to expect that there will be a range of adjustment challenges along a range of severity. Over 30 percent of combat veterans meet the strict criteria for PTSD or depression but many more have lesser but impactful symptoms. The most common indicators of significant difficulties are: sleep difficulties including nightmares; depression including isolation and lack of energy; substance abuse; explosive anger and physical violence, relational difficulties, and suicidality.

National and local resources are an Internet search away, including hot lines for veterans and families. Locally, our Vet Center has support groups and there are other experiences to help veterans to reintegrate to the community.

PTSD is not a lifelong condition if one seeks help. Our local VA and Vet Center has capable clinicians, there are psychotherapists with trauma expertise and EMDR (Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) therapy trained clinicians locally, many who work with veterans. EMDR therapy can often help veterans safely “unpack” traumatic memories and better come to terms with the events of the past.