Giant Steps: Walking on the Moon with Bill Lee

"They asked me about mandatory drug testing. I said I believed in drug testing a long time ago. All through the sixties, I tested everything." —Bill Lee aphorism

By Mike Briotta

PRIME Editor

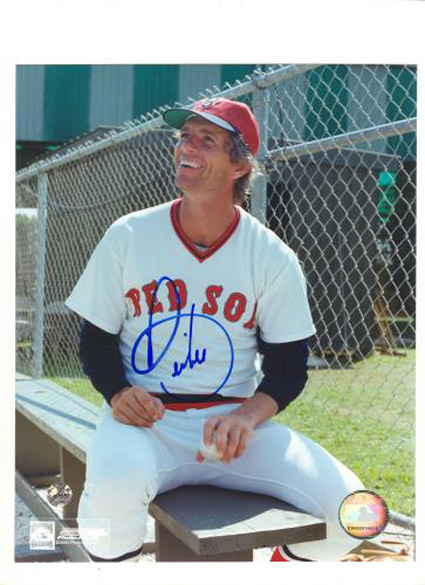

When former 1970s Boston Red Sox pitcher Bill "Spaceman" Lee visited the Basketball Hall of Fame this summer as a guest speaker, he appeared like an interstellar traveler who only occasionally touches down on Earth.

It's an outrageously sunny day in Springfield. Looking up, Lee calls it a "Simpson's sky": cool cerulean blue, dotted with perfectly white, puffy clouds and blazing sunshine. The "Spaceman" remembers once seeing a parody drawing of Che Guevara wearing a Bart Simpson T-shirt. Someone reminds him that, coincidentally, he's standing in Springfield, a city whose name coincides with the fictional home of the characters on "The Simpson's" cartoon TV show. He smiles broadly in recognition.

Inside the Hall, on the "Court of Dreams," Lee recounts tales of the baseball days of yore, of Red Sox legends like Carl Yastrzemski and Luis Tiant. Though weathered, his tales never seem to tarnish. They are continually made fresh through his re-telling. He dispenses advice to a crowd of children on school vacation, faithful Sox fans, and wayward journalists. "You don't want to be Ted Williams," he says. "You don't want to be Larry Bird. Be as good as them, but be your own person. Don't put your eggs in someone else's basket."

His shaggy silver mane pokes out of the sides of his baseball cap. A snowy white goatee crests his chin. Lee sports a perpetual tan, and he's outfitted in a short-sleeved dress shirt and sandals. He's a baseball messiah who looks like he just got back from the beach.

The former Red Sox pitcher continues, "To your own self be true. Someone famous said that. Do you know who it was?" A precocious member of the audience answers, "Shakespeare!"

Nope, Lee says, "That was Jiminy Cricket."

Of course, the kid is actually right. Jiminy Cricket's famous aphorism is a close second: "Always let your conscience be your guide." But nobody in the crowd minds the misstep. Everyone seems to understand that things can look a bit different when viewed from space. Lee continues, "Cervantes and Shakespeare died on the same day. Did anyone know that? I am Don Quixote, because I joust at windmills. I root for the underdog."

In the middle of another conversation, Lee suddenly spouts a poem that sounds remarkably like William Carlos Williams. That is, if Williams wrote about being a famous southpaw instead of the importance of chickens and wheelbarrows. It's a haiku about a wet line drive, rolling along the infield grass, and ends with emphasis on the pun "Wrigley."

Lee pauses for a moment, basking in his Renaissance Man status. "That's poetry," Lee says, admiring his most recent quote as it hangs in the air. "I speak in full, lyrical paragraphs. It's similar to song lyrics or poetry." He continues, "People say I'm cocky. Well, that's good. Don't be obnoxious, but it's good to be cocky."

He's not wrong about the poetry of his sound bytes. Singer-songwriter Warren Zevon crafted an ode to the pitcher in "The Ballad of Bill Lee" that used the athlete's quotes as lyrics. Zevon crooned about Lee, paraphrasing some of the pitcher's most famous quotes about baseball: "You're supposed to sit on your ass. And nod at stupid things. Man, that's hard to do. And if you don't, they'll screw you. And if you do, they'll screw you too."

Much like his hero Quixote, Lee's image is entirely subjective. Some see the aging pitcher as a clown prince, where others find an unlikely sage. Many who remember his pitching days in the big leagues would agree that the world will probably never again witness such a character he's at once a baseball poet, a countercultural activist, and a smirking jester pointing out the emperor's lack of clothing.

Nowadays, Lee is a retired country gentleman, living in a virtually nameless place, who sets out each day to chart his own chivalrous adventures. His devotion to a unique cause is unquestionable. Just say the word, it seems, and he'll gladly take you along for the ride. After all, the assistance of a squire is vital when jousting at windmills on the plains of La Mancha.

Extra-Terrestrial

When he was just a kid, his dad wrote something on his baseball: "Hustle." The simple imperative paid off. During his college days, Lee led the University of Southern California baseball team to a winning 38-8 record and a national championship. He was later picked up by the Sox in the secondary free agent market where, as Lee puts it, "You have no value." The southpaw would have to prove his value in Boston, and later in Montreal.

On the mound, he threw a quirky pitch referred to by himself and others as the "Leephus," "spaceball" or "moon ball" pitch. The free spirit was also an American League All-Star in 1973. He spent a decade with the Sox, throughout the 1970s, when Lee was in his 20's. He pitched more than 1,500 innings with Boston. According to a book by baseball scribe Peter Gammons, Lee earned $80,000 pitching for the team in 1975 alone.

Following the 1975 season, he spent two weeks that off-season in Red China as a goodwill ambassador, and came away with some interesting insights and stories. He spoke in defense of Maoist China, population control, Greenpeace, school busing in Boston and anything else that happened to cross his mind. He ate health food and practiced yoga. Lee claimed that marijuana use made him impervious to bus fumes while jogging to work at Fenway Park, and the weed was also an ingredient in his morning pancakes.

Asked about his status as a counter-cultural figure, he quips, "I'm not very cultured. I'm an Earth-first person. I'm sans frontieres, which means without borders." Lee describes the sojourn he made to Cuba. "I loved it," he says. "I didn't know much about it until I got there. Contrary to what's said, they love America. The baseball was fantastic."

He adds a soliloquy from the pitcher's mound on the revolutionary island: "I check the runner at second... check the runner at second again... and then three pigs run through the infield." Lee continues, "There was a bull in right field, and when you hit the bull the ball stops. It was like he was playing outfielder."

Suddenly, he flashes back to a Major League game in the mid-1970s when he threw a dozen straight "junk" pitches. "They said I was making a mockery out of the game," he recalls of the rain-soaked outing. "But I said, where in the rule book does it say I can't throw 12 pitches at 15 miles per hour? A lot of guys couldn't hit that stuff." Like the rest of his life, slow pitching in the rain was a natural act of defiance against the dogmas of baseball.

Lee struck out batters by being crafty, and maybe a little bit crazy, rather than by sheer speed alone. He adds, "Back then, we threw every fourth day. I was in the bullpen for five years. I wasn't a starter yet. I was good, but I was a left-hander who didn't throw hard. If they used a radar gun like they do today, they would have to take the batteries out. They would think it's broken."

Asked about the last time he spoke with his former Red Sox manager Don Zimmer, Lee replies, "It was 1984 in Chicago. He said 'Get out of my locker room you no-good Pinko Commie. Those were the exact words he used." To say that he never liked Lee's free-spirited ways would be an understatement. As a result, Lee and his teammates never much cared for Zimmer either. "Zimmer didn't like us," Lee says, "And he put us in the dog house."

Despite his views about off-the-field matters, his teammates players respected Lee. They knew that his foolish antics took pressure off the team, and that his attitude on the field was all business. He wasn't afraid to criticize management, causing him to be dropped from both the Red Sox and later the Montreal Expos.

Long after a falling out in Beantown in the late 1970's, all is well these days between Lee and the Red Sox. "Oh yeah," Lee says. "[Sox president] Larry Luchino, [team owner] John Henry. Everybody there loves me. Of course, they still don't know what compartment to put me in." They did, however, offer him the ultimate olive branch, by inducting Lee into the Red Sox Hall of Fame in 2008.

He still occasionally exchanges phone calls with the Red Sox front office. As if to sum up his view of the universe, Lee describes the metaphysical, otherworldly, and existential message that awaits callers to his cell phone: "You've reached Bill Lee's voicemail. I'm not here. You're not here. No beep. No message."

2011: A Baseball Odyssey

These days, Lee says he loves to shoots hoops in the town where he lives, a small village in Vermont. His basketball teammates are dairy farmers who kick off their work shoes caked with cow manure along the sidelines before lacing up their sneakers. It's a tiny basketball court, that stinks of the barnyard, away from most of civilization. And there's nowhere else Lee would rather be on a sultry New England evening.

For a guy with a reputation of being "out there" orbiting among the celestial bodies, he's about as down-to-earth as anyone gets on this planet.

The 64-year-old is still actively playing baseball, pitching at charity events throughout New England. "I pitched 17 innings last week," he says. "Tomorrow at noon I pitch in Vermont, and Monday through Wednesday I pitch in Cooperstown, New York." The Cooperstown isn't an official Baseball Hall of Fame gathering, but rather Lee is part of an Ohio group that rents a field there to play ball. He also pitched a game in Easthampton this summer, a fund-raiser to support the local fire department.

As if to simultaneously honor and disrespect a longtime nemesis, Lee carries around a baseball card of Craig Nettles in his wallet. "I keep this in my wallet at all times," he says, pulling out the well-worn cardboard rectangle with dog-eared corners. "On the right cheek of my ass. Abraham Lincoln said to keep your friends close and enemies closer."

For explanation, Nettles broke Lee's collarbone during an on-field scuffle in 1976. At the onset of the brawl, Nettles tackled Lee from behind. When the fracas resumed, he swung at the pitcher and then crushed him when they went down in a pile of battling players. Lee was arguably never the same pitcher again. The incident added to the storied Yankees Red Sox rivalry.

Maybe the card means something; maybe it means nothing at all. It's all part of the Bill Lee enigma. He also keeps a tattered hockey card of National Hockey League great Frank Mahlovich of the Toronto Maple Leafs in there too, among the images of other star athletes. He's enamored with the legends of not just his game, but of all great athletes.

"Wayne Gretzky had eyes in the back of his head," Lee says, "and Bill Bradley has a book called 'A Sense of Where You Are.' It's mandatory reading. I like to say: wherever I go, there I am."

He adds, seemingly channeling Yogi Berra: "When you come to the fork in the road take it; These are Zen Buddhist sayings for athletes."

Lee also owns a bat company named The Old Bat Company, and is the subject of the film "Spaceman: A Baseball Odyssey." In 2003, filmmakers gathered a guerrilla film crew and joined Lee on a barnstorming trip to Cuba. In 2010, Lee pitched almost six innings for the Brockton Rox, picking up a win that made him the oldest pitcher to appear in or to win a professional baseball game.

Even today, his boundless energy is self-evident. Just try to follow Bill Lee through a crowded basketball court, where families are shooting hoops at sporadically set-up baskets. The Hall of Fame court is teeming with running, screaming, basketball-shooting 11-year-olds. Sneakers squeak sharply on the basketball court in a cacophony of sound. It's a tangled mess of flailing limbs and flying objects.

Lee pays no mind. He deftly zips in and out, taking a random walk that occasionally breaks into a full-borne gallop. He bobs and weaves through the crowd toward whatever will next entertain his furtive mind. Is he shooting hoops? Headed toward the bathroom? About to burst into flames, spontaneously combusting from all the excitement? Who knows? It's tempting to believe that just about anything could happen.

The pitcher bounces around the room like an electron about to escape from its atomic shell a free radical. Lee grabs a basketball and fires a perfect pass through a momentarily open lane on the court, toward his wife Diana. She smiles and calmly returns the ball to a nearby rack. She takes his hand, and they walk through the exit, emerging into the seemingly radioactive glow of a cartoonish Springfield sun. PRIME