Bill Rasmussen: Architect of ESPN

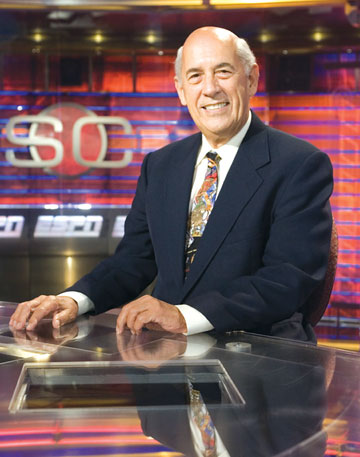

Prime photo courtesy of ESPN

By Mike Briotta

PRIME Editor

Prior to about 1980, the "thrill of victory and agony of defeat" made only weekend appearances on TV sets nationwide. If you were a lucky sports fan, maybe you caught a single televised gridiron game early in the workweek: Monday Night Football.

Otherwise, weekday sports on TV were limited to glossed-over highlights during the 11 o'clock newscast.

Enter former Channel 22 sportscaster Bill Rasmussen, who would carve out a niche for himself as the single most influential pioneer in cable sports television. The former Wilbraham resident created the global ESPN franchise in the late 1970s - ensuring that American sports fans would never again be satisfied with sporadic, local coverage of their favorite teams.

Former local sportscaster Bill Rasmussen is the founder of ESPN.

Before ESPN, television stations didn't carry out-of-town games. Hoping to watch your favorite team playing on its West Coast road swing? Forget about it. The lion's share of March Madness contests, college football games, and other NCAA events? Sorry.

Watching sports on TV back then was a far cry from the nationwide, round-the-clock coverage we have today.

Rasmussen's book about the company's early days, "Sports Junkies Rejoice" is appropriately titled. Without ESPN, the "Worldwide Leader in Sports" there would be no joy among millions of fans.

Sports nuts have come to rely on the constant updates of the network's 24-hour programming. Its highlights show "SportsCenter" hits to all fields, covering virtually every major sports league.

"If you have an idea, pursue it. Lots of them don't work, but some of them do," Rasmussen said of dreaming up ESPN. "It was a good thing that I had no other options."

A Sporting Chance

Rasmussen's got his television start when he took what he thought was a sports gig at Springfield's ABC affiliate at the time, WHYN-TV. As it turned out, the station manager wanted him to read the weather. Rasmussen was undeterred.

He agreed that he would read the weather, but figured he would sneak in some sports coverage too.

"The day I walked in, the guy said 'We're not going to do sports. You're going to do weather tonight,'" Rasmussen recalled. Since the pay was a meager $10 per show, he decided to flip the script.

"I really did want to do sports, so I would change the weather into sports a little bit," he said. "For example, I would say, 'In Pittsburgh tonight, where the [Springfield] Indians are playing, it's snowing.'"

Although he was a new face and a pioneer in cable TV, it would be disingenuous to say that Rasmussen was a sports newbie when ESPN first got national attention in the late 1970's. His local roots also included a decade-long stretch as sportscaster and news anchor with WWLP-TV, local Channel 22.

By the time he conceived of ESPN, he had already worked with a list of famous athletes including the hockey legend Gordie Howe, former Springfield Indians owner and hockey veteran Eddie Shore, NHL coach Johnny Wilson, and professional boxers including Willie Pep, Rocky Graziano, Jake LaMotta and Jersey Joe Wolcott.

Along the way to cable TV, Rasmussen also interviewed Bob Cousy and Sam Jones of the Boston Celtics, Red Sox star Carl Yastrzemski, and "the incomparable" boxer Mohammed Ali when he was still known as Cassius Clay.

Through another half-hour television show broadcast by WHCT-TV in Hartford, Rasmussen and his son Scott also got to spend time with Olympic skiers, famous golfers, and well-known softball pitchers. All of this experience on both sides of the camera would later lay the groundwork for ESPN.

Of course, Rasmussen knew that a career related to professional athletics could be tumultuous. He left Channel 22 in 1974 for a gig working for the New England Whalers of the World Hockey Association.

The Whalers experience lasted a few years. Ironically, getting fired suddenly by team owner Howard Baldwin was probably the best thing that ever happened to Rasmussen's career. It was the turning point event that prompted Bill and his son Scott - who also had a job with the Whalers - to begin searching for greener pastures.

According to Rasmussen, his termination was a result of the hockey team performing badly (something he had nothing directly to do with as communications director). Rasmussen got a rude awakening, coupled with about a month's severance. Adding insult to injury, his ties were severed that same day with former friend Howe, a hockey star who was winding down his professional career with the Whalers.

"It was Memorial Day Weekend in 1978 when they fired me," Rasmussen vividly recalled. "It was a losing season [on the ice] and they fired everyone who didn't skate for the Whalers. Even though we weren't the ones who missed the playoffs!"

Power Play

It would be false humility for Rasmussen to say he was simply in the right place at the right moment, though he does credit fate with playing a hand in the success of his nascent enterprise.

The cable TV pioneer was among of the first wave of speculators to get access to a round-the-clock satellite transponder for the buy-in price of about $30,000 in 1978. Within two years, that same privilege was being sold for the princely sum of $10 million per transponder.

"They couldn't give them away at that time," Rasmussen joked about the RCA satellite transponders. "Now they cost $800,000 a month."

Just getting the technology and legal rights to reach future subscribers wasn't enough, however. There were much larger business hurdles to be cleared. Once he had the 24-hour-a-day transponder, he had to put it to good use - and quickly. But what could fill all those hours?

The original name of E.S.P. Network reflected that uncertainty. It was named "Entertainment and Sports" because he worried that sports alone might not be enough to fill the void. But Rasmussen somehow succeeded where others had failed, bringing complete sports coverage to cable TV.

"When we proposed 24-7 sports, everybody said we couldn't do it; we'd never find the programming," Rasmussen said of the tenuous early days when ESPN had satellite rights, but before it officially launched its programming. "According to FCC rules, they had to keep us. We had our shot and they honored it. We were lucky."

Fortunate certainly, but Rasmussen was also very hardworking. Within one year, they somehow secured the deep advertising pockets of beer makers Anheuser-Busch, got the necessary approval of a reluctant NCAA governing board, and obtained the financial backing of Getty Oil.

The latter company would offer the entrepreneur cash reserves at a steep price: an 85 percent controlling stake in his company. Getty would bail him out financially, at the cost of his ESPN ownership.

So it was a bittersweet triumph that when ESPN finally reached television sets in September of 1979, that Bill Rasmussen and his son Scott knew they were no longer at the helm of the ship that they themselves had built from the ground up.

The paint was still drying on his Bristol, Conn. headquarters when the company founder realized that Getty didn't want him around much longer. New management soon began pushing Bill and Scott to the periphery.

Company cars were revoked. Salaries shrank. Bill was asked to step aside from the top spot, so that Getty could bring in a former head of NBC sports to run ESPN.

"We didn't have a choice," he said of the difficult time. At the time, ESPN didn't have enough cash to stay afloat without Getty's fateful involvement, even though the oil company's buyout would prove fatal to the Rasmussen's' control of their company.

Despite the circumstances, the first few moments of watching ESPN programming begin that night were magical.

"It was an electrifying moment when we first when on the air," Rasmussen said. "Sports cuts across all demographics. Rich or poor, male or female, we're a nation of sports fans. People love their sports."

Extra Innings

Getty Oil gave Rasmussen his golden handshake long before ESPN became a household name; long before the creation of ESPN The Magazine, and prior to the conception of merchandising opportunities like the ESPN Zone in Las Vegas.

His original target market was two million homes, a huge number of customers at the time. When he was ushered out, the company had yet to fulfill its promise of 24-hour sports (a goalpost they quickly reached in April of 1980).

ESPN's viewership would soon triple to six million homes, then 12 million a year later, then 20 million the next year, reaching 30 million viewers by 1983. From its single beer advertiser at the inception, more than 300 advertisers signed on within four years. ESPN's ad revenue now averages $441 million with an ad rate of nearly $10,000 per 30-second slot.

Local advertisers, who at first didn't want anything to do with his product, witnessed the growth of ESPN and knew they couldn't ignore the opportunity.

"Today, local advertising [on cable] is a multi-billion-dollar industry," he said. Rasmussen added regarding the brand loyalty of viewers, "I don't think anybody is going to touch them. The number one recognized brand in the world is between ESPN, Coca-Cola and Pepsi."

Though he now resides in Seattle, Rasmussen's local ties remain strong. He's an inductee into the Enfield Athletic Hall of Fame in Connecticut. Rasmussen was acknowledged by that town with a day in his honor in 2008. Bay Path College in Longmeadow has also hosted him as a speaker. As he put it, "I still have a lot of local connections here."

He's an avid golfer, and a frequent participant in celebrity charity golf events throughout the country. His book was recently published in its first-ever paperback edition.

Rasmussen's recent endeavors included the introduction of College Fanz, an online college sports community in 2007.

He was also the chairman of SportsatHome, a sports-themed game Web site that offered an array of virtual sports stadiums and games to play online.

Rasmussen said he's as shocked as anyone that the city of Hartford wants the Whalers back as an NHL franchise, since the team rarely made the playoffs and seemed to have an unsupportive fan base.

"I'm really surprised at that," Rasmussen said of the Whalers rejuvenation effort. "I didn't get the impression they supported them very well before. I guess it's probably not going to go anywhere."

Some of his favorite haunts locally were Blunt Park and Forest Park, and he tries to return to this area whenever possible. He lived in Wilbraham during his time on the air with Channel 22.

Rasmussen remains on good terms with the ESPN corporate juggernaut, and frequently does ESPN radio interviews discussing his book and other topics. He's also a frequent speaker at college campuses.

The entrepeneur is turning 78 soon, but still relates to the quick-thinking college crowd - many of whom can't imagine a time before ESPN.

"I'm speaking this October in Fort Wayne, Indiana at a college," he said. "It's a lot of fun. I'm looking forward to it."

He's proud that 40 of his original employees from 1979 remain employed at ESPN today. That's a testament to how well he built his company to withstand the test of time.

Rasmussen is thrilled to say he was the pioneer who conceived of ESPN. He built the monolithic sports empire from the ground up. It's his creation that still beams signals to an orbiting satellite, which scatter back down to points all over the earth.

"It's been a long run," he said. "It turned out to be quite a success. I was born during the Depression, and I can still hear my father telling me, 'Work hard, and good things will happen.'" PRIME